Crystal vs. Glass: Primer for the Hobbyist

- Vanserai, Ltd. Co.

- May 29, 2022

- 9 min read

Imagine this: you’re on vacation - somewhere full of history and tons of opportunity to explore - and you’ve found yourself a cute, hole-in-the-wall consignment shop. You step in the door and wow. Everywhere you look there’s something. You wander through, though nothing quite catches your eye. Then, you step through an archway and your jaw drops. Before you is a warren of shelves filled to the brim with glass of every shape and color. Alone on one side of the room is a table of clear glass. Slightly dusty and unassuming, you figure it’s the easiest place to start but when you get there you just stare.

Where do you start? How do you tell what’s “good” and what isn’t?

Welp, that’s why I’ve created the primer below to help you mid-shop so you can walk away with a bundle of treasures you love and are confident in.

Glass 101: What’s the Difference?

Glass has been a thing for a minute. Like, when we say minute, we mean a minute. Humans started out using what we could find hanging around. This was more often than not a black, brittle volcanic glass called obsidian. But being the savvy creators we are, we gradually figured out how to make our own.

Around 5000 BC, one of the first claims to glass creation was in Syria as noted by the Roman philosopher Pliny. Archeologists disagreed, of course, and claim that evidence points to the arrival

of man-made glass in Mesopotamia in 3500 B.C. and glass vessels in Egypt around 1500 B.C.

Despite a bit of an on-again-off -again thing as civilizations rose and fell, glass creation and manufacturing would become a staple of our global culture by the 1st century B.C.

Glass falls into two broad categories: Soda-lime glass and amended glass (glass with more than just silica dioxide, lime, magnesium oxide, and aluminum oxide.)

Soda-lime is your basic B. glass: it’s used for pretty much everything and is the base for things like tempered glass, laminated glass, safety glass, etc. Your fancy

kitchen canisters? Soda-lime. Windows? Soda-lime. It really is everywhere.

Another similar type of glass you might run into is borosilicate glass. This is most often used for cookware or when an item may be exposed to high temperatures. It is the (much) younger cousin of our soda-lime glass, having only been around since the late 19th century.

There are several more modern glass types that are used in both practical and decorative glass manufacturing. I’ve listed the most popular ones below with a quick description.

Optic Glass:

Also called optical or ophthalmic crystal, this is the glass used in eyeglass, microscope, and telescope lens, among other things. It is heated to an extremely high temperature and then cooled extraordinarily slowly. This creates a glass that is incredibly hard, clear, and resistant to scratching or chipping. It comes in various grades with grade K9 being used more for manufacturing( it has a tendency to tarnish and yellow over time) and grade A being used as a decorative glass replacement for lead crystal. It is actually much more expensive, oz to oz, than lead crystal. This glass has only been in commercial use for the last 30 years or so.

Uranium Glass:

This is glass that has had uranium, usually in the form of uranium oxide diuranate, added to the glass before pouring or shaping. It was added at a rate of about 2% per item weight but during the glass craze of the 20th century up to 25% was added. Uranium glass fell out of widespread use after commercial uranium use was curtailed during the Cold War. The glass is categorized by its yellow-green glow under ultraviolet light and its noticeable sensitivity when measured by a Geiger counter. Colors range from Yellow-white to blue to neon green.

Milk Glass:

Blown or Pressed, Milk glass is a white opaque or translucent milky glass. Though often seen in white, it does come in a variety of shades including pink, blue, yellow, even black. It was first created in Venice during the 16th century and saw a resurgence in the early 20th because of its ability to disperse light. It is also called “opal glass” and was used as a porcelain substitute before being collected for its own merits.

Carnival Glass:

Molded or Pressed, this glass has been painted with iridescent shimmer that had it being dubbed “the poor man’s Tiffany” when it was first released in the early 20th century. It was used mostly by households that were unable to afford electric light as it has the ability to catch even the dimmest light and refract it beautifully. It reached its peak popularity in the 1920s but wasn’t called “carnival glass” until collector’s noticed it in the 1950s, causing a resurgence in the style, when it was given out at festivals, carnivals, and as prizes at parties. It comes in a variety of styles, patterns, and colors, with rarer color combinations demanding extremely high prices from collectors.

Fused Quartz:

Fused quartz is also called fused silica as it consists mostly of silica, or silicon dioxide, in its non-crystalline (amorphous) form. This gives it an extremely high melting and working temperature which in turn makes it highly undesirable for most commercial applications.

Fused quartz is silicon dioxide in its glassy form and is used mostly for semiconductor fabrication and lab equipment, specifically highly-specialized lenses and items requiring the transference of ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths.

You will not find this on just any old thrift store shelf but if you are looking at places that sell old lab equipment or at a liquidation sale of the same you may run across this expensive and rare glass.

How It Sings and Shines: 3 Quick Ways to Identify Crystal (and 3 Slower Ways...)

Let’s be clear about one big major bit of misinformation: crystal IS glass. It is glass that has had a certain percentage of lead oxide added into the potash or soda. When we’re talking about crystal we’re still discussing glass. It has all the properties of glass with a little extra-extra added on, that’s it. This means, as you’ve probably realized, it’s rather hard to determine the differences between the two varieties right off the cuff.

When we walk into a store like the one presented in the beginning of this blog and are faced with having to make a decision quickly and confidently there are six things to look for: weight, sound, thickness, cut, shine, and clarity. Of these six, three (weight, thickness, and sound) require you to handle a piece to some degree and there are times when that is just not possible. I’m going to detail how to recognize leaded glass by these six factors and then how to use that knowledge when it matters, even if there’s no picking up the merch.

Shine: Also called “refraction,” this is the degree by which light is split apart within the glass and shot out the other side as that dazzling display of dancing colors. Leaded glass is, by far, the best material for crisp, clean refraction. It will sparkle like a thousand diamonds in even the lowest light or under a layer of dust. Be aware that the higher the refraction rate also means the higher the percentage of lead. We’ll speak more on this later.

Note: Please remember that optic glass will also refract with gusto and, if you are unsure of the age of the piece, don’t immediately assume from this point alone that the item is crystal.

Clarity: This is how easily light is able to pass through both cut and uncut pieces. In general, soda-lime and other non-leaded glass will begin to lose its clarity as it ages, growing foggier with the more time that passes. The cheaper the glass, the less time that will need to pass before the clarity is affected. Leaded glass will maintain its clarity indefinitely, if it remains undamaged.

Cut: Cut has a great deal to do with the manufacturing process required for cut crystal and less about the material’s innate qualities. When you find cut glass, the edges of the cuts are often sharp and brittle. This is caused from the item not truly being cut but the molten glass being poured into a mold. Soda-lime glass is too fragile and expensive to shape and those edges are left as they are after they’re removed from the mold. Leaded glass is sculpted when still hot, similarly to blown glass, creating smooth, rounded edges. It is softer and has a lower (ish) working temp, which makes it easier to handle, at least in terms of manufacturing. This does make it more expensive as the labor costs are higher.

Note: While the practice is not common, non-leaded glass has been softened and refined by hand, particularly in antiquity. Be sure to use this factor in conjunction with the others in this list as confirmation.

Now we have the remaining three which you may not be able to use. The unfortunate thing is these are the ones that really check the boxes. If you can convince the store proprietor to let you handle the pieces, please do. Usually they hover so there’s that awkwardness to contend with but you’ll get the pleasure of using your new skills. That’s always nice.

Sound: If there is one thing about crystal that touches me the deepest, it’s the sound it makes. There is nothing like it the world over and to have it sing for you with a simple tap of your fingernail against the side is pure joy. The level of lead, the general composition of the glass, and the physical shape will alter the tonal range of individual pieces but the more lead there is the more eager it’ll be to sing for you and the more resonant the note. Soda-lime glass swallows sound and will produce a low tonal thud, even the fancier milk, uranium, or carnival glasses.

Thickness: We’re going to circle back around to the manufacturing process. Remember how we said that leaded glass is sculpted and not molded? Well, this practice also translates to thinner glass overall, as the glass is pulled and shaped like dough, thinning as it’s pulled into shape. With its high working temp, soda-lime glass has a tendency to be left to its own devices, leading to glass pooling with the force of gravity and ultimately being thicker overall. Crystal is thinner and finer.

Weight: If you had two wine glasses of the same size and type, one in each hand, which would you think would be heavier? The soda-lime one, right? The crystal is thinner glass so the obvious conclusion we would most come to is that it would be “lighter.” But, in fact, lead crystal is always at least an ounce or so heavier than anything of a comparable size made of soda-lime glass. Remember, lead is an extremely dense material and that same density would translate to any object into which it was incorporated.

These six factors are an excellent starting point for determining whether the piece you’re eyeing is lead crystal or regular glass but they are just the basics. There is one other huge factor that comes into play and that is where the piece was produced. Many thrift finds don’t have makers' mark stickers anymore, or the laser mark has worn off, or it is so old that there never was a mark to start with and we have to get fancy to figure out the origin of manufacture.

Listen up, yo: Point of Origin Matters

The top five producers of lead crystal in the world as of 2019 are the European Union (The UK, Northern Europe, the Germanic States, and traditional Bohemia are included in this category) France, the UAE, Slovenia, and China. Traditionally, Eastern Europe, Northern Europe, the UK, France, and the United States were the home for the top crystal companies. Each of these countries, and the manufacturers within those countries, have different standards for their crystal.

For example, crystal can hold up to 40% lead in its makeup before it becomes unsafe. Most European producers required their crystal to have no less than 10% and no more than 30% in order for the piece to be labeled as “fine crystal.” The United States, on the other hand, wanted to make crystal more accessible to the newly emerging middle class and desired the lead that was being used in crystal to go to other industrial manufacturing so they changed their restrictions on crystal. A piece that had 1% or more lead oxide was considered “fine crystal” starting in the late 19th century.

All this to say, if you’re shopping in the United States you’ll probably find it more difficult to determine whether the piece you’re holding is crystal. You’ll have to use several of the above factors plus any extra knowledge you might have of regional designs or patterns particular to one company or another to make your final determination.

Each of the locales above has their own styles and pattern designs specific to both the region and the manufacturer. Be sure to become familiar with some of the bigger names in crystal production, such as Waterford, Bohemian, Lenox, Baccarat, Tiffany, Lalique, and Daum, to better pinpoint those differences as you shop.

Let’s Try It!

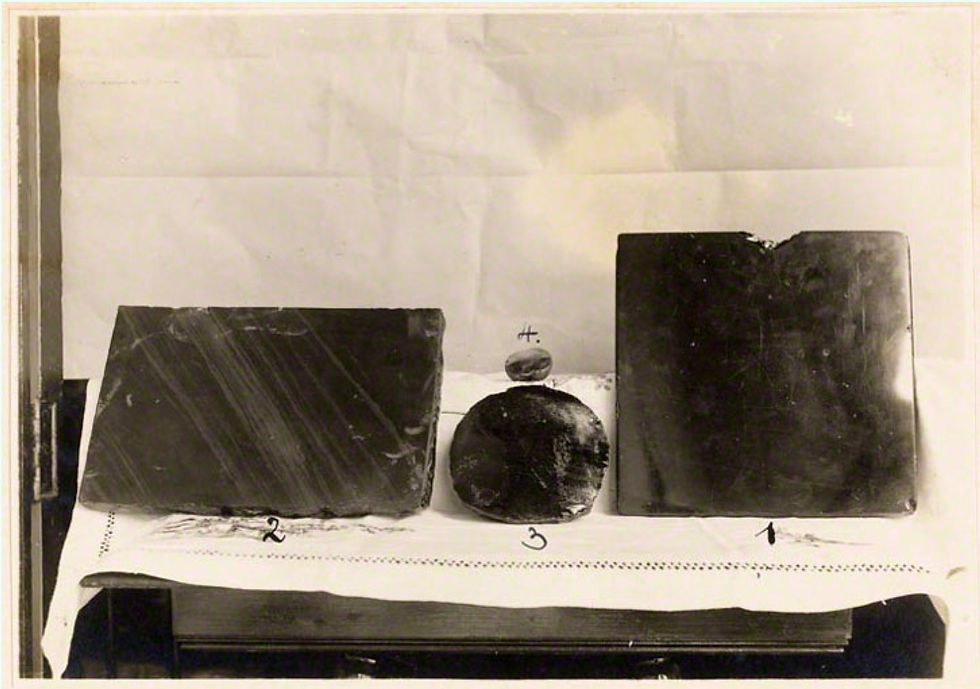

Now that we know what we’re looking for and how to identify it, let’s see it in action. Below, I have the images of three glasses. I’ll walk through how I’ll determine which is simple glass and which is lead crystal.

The piece on the left is a traditional formal cut “glass” wine glass by a high end brand stemware manufacturer. The piece in the center is smoother “glass” that has been engraved with a series of designs in repeating patterns with a sharp cut rosette on the stem. It is from a highly respected artisan glass brand. The piece on the far right is another formal cut “glass” wine glass that is currently unbranded.

Step 1: Shine

Step 2: Clarity

Step 3: Cut

Cut Crystal vs Cut Glass

Etched Crystal

Step 4: Sound

Smooth Crystal vs Smooth Glass

Cut Crystal vs Cut Glass

Step 5: Thickness

Step 6: Weight

Conclusion:

The world of crystal is wide and varied. You’ll never know what you’ll find where and looking is half the fun of it. Using these steps, you’ll be able to confidently assess the glassware in most any vintage store you enter, making the search just that much more exciting.

Comments